The Legend of Silk and the Silkworm Heist

The Chinese Empress who accidentally discovered silk, the Byzantine monks who pulled off the Silkworm Heist, pine pollen cakes and sweet wine cakes.

Silk. Lustrous and sheer, a pleasure to see and touch; the substance of wealth, the fabric of scandal. And so painfully, deliciously lucrative.

The Discovery

According to legend, it was a Chinese empress who first discovered silk. Recorded by no other than Confucius, the story of silk starts around 2700BC! That’s right, almost five thousand years ago.

According to his tale, Empress Leizu of China discovered silk by accident when a silk worm happened to fall in her cup of tea. Warm water is what makes the silk on the cocoon of a worm soften and the thread loose.

She noticed this when she lifted the cocoon out of her cup and in a moment of wonderful inspiration, decided to try to weave a fabric out of this strange material, which appeared to be a single long strand of thread.

Empress Leizu persuaded here husband to give her a mulberry tree grove, so she and her attending ladies can give a try to growing silk worms.

According to the legend, we can thank the empress for the invention of the silk reel, which joins fine filaments into a thread strong enough for weaving and the first silk loom.

Empress Leizu is known as the “Silkworm Mother” even now in modern China.

The process of farming silkworms, as well as the harvesting of fibres and weaving them into silk fabrics was and remained a process entirely restricted to women in China for a very long time.

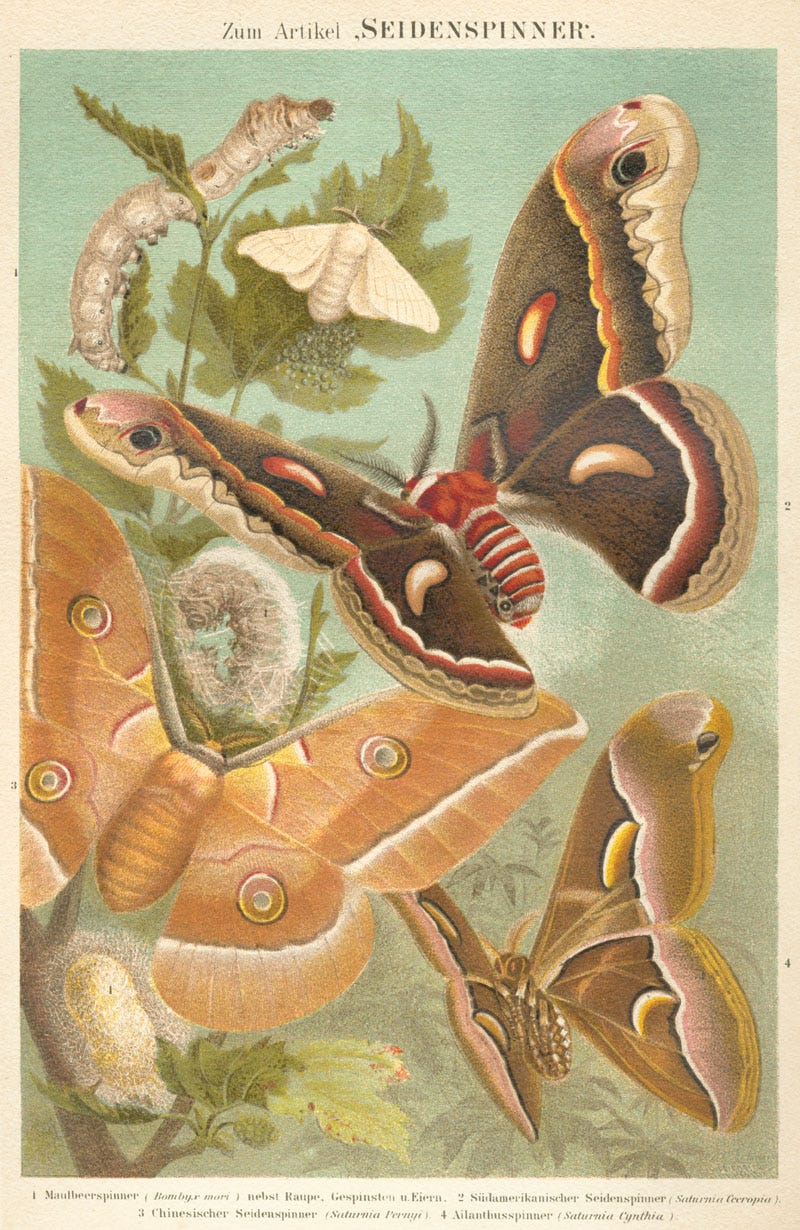

Not only that, China kept a strict monopoly on silk production for thousands of years. The tree preferred by the silkworms, the Mulberry is native to China. There was a serious ban on the transport of silkworms or their eggs to other countries, under the penalty of death.

The Silkworm Heist

Fast forward to about 550 AD. Justinian is Emperor in Constantinople and silk has been dripping from classical bodies for a millennium. This expensive fabric came from the East.

Silk could come to the West through one of two routes:

in red, the famous Silk Road

in blue, the shorter and busier Indian Ocean route, which exploited the monsoon winds to connect Alexandria with the ports of western India and Sri Lanka.

Chinese silk seems to have flowed along both routes, though most probably reached the Roman Empire via the easier Indian Ocean route.

Eventually the problem was the trade deficit with China (yes, even back then): silk kept coming West, while gold and silver kept going East in exchange. That, and the general unrest of the period compounded with what was maybe a personal ambition, Emperor Justinian I started pondering how to come up with a solution to the silk problem.

Procopius of Caesarea was a prominent late antique Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Procopius became the principal Roman historian of the 6th century, writing the History of the Wars, the Buildings, and the Secret History.

The writings of Procopius are the primary source of information for the rule of the emperor Justinian I. It is in one of his writings that we gleam some details about how Justinian I planned to get his hands on silk.

As Procopius says: "About the same time [553 CE] there came from India certain monks; and when they had satisfied Justinian Augustus that the Romans no longer should buy silk from the Persians, they promised the emperor in an interview that they would provide the materials for making silk so that never should the Romans seek business of this kind from their enemy the Persians, or from any other people whatsoever..." (Wars 8.17)

"[The monks] said that they were formerly in Serinda, which they call the region frequented by the people of the Indies, and there they learned perfectly the art of making silk. Moreover, to the emperor who plied them with many questions as to whether he might have the secret, the monks replied that certain worms were manufacturers of silk, nature itself forcing them to keep always at work..."

So the story goes that a bunch of monks, possibly Nestorian missionaries, offered to help out. Two monks, who had been preaching Christianity in India, traveled to China and spent some time there, studying the intricate methods of farming of silkworms and the making and weaving of silk.

Then in 552 AD, they went to the Emperor and told him that they could procure silkworms for him from China. We do not know what or if they were promised something in return.

They traveled to China one more time and somehow got their hands on a few silkworms without being caught and arrested by Chinese authorities. They then proceeded to hide the worms inside their bamboo walking sticks while they traveled out of China towards their destination in Constantinople.

And how did they keep the silkworms alive for all this time, considering they of course could not just take a flight out of there? As Procopius very helpfully informs us:

"[The monks told Justinian that] the worms could certainly not be brought here alive, but they could be grown easily and without difficulty; the eggs of single hatchings are innumerable; as soon as they are laid men cover them with dung and keep them warm for as long as it is necessary so that they produce insects."

However they did it, it definitely seemed to work, as silk production started shortly after this expedition in Constantinople, Beirut, Antioch, Thebes.

The successful Silkworm Heist allowed the Byzantine Empire to establish a new monopoly on silk in Europe, which was a strong foundation for the Empire’s economy for the next 650 years or so.

Silk clothes, especially those dyed in imperial purple, were almost always reserved for the elite in Byzantium, and their wearing was codified in sumptuary laws.

Now on to the good stuff. Because I am talking about silk, I wanted to find something delicious and rare from both ancient China and Byzantium. After quite some time searching and combing the small recesses of the Internet, I found pine pollen cakes, and sweet wine cakes. Recipes are below.

Pine Pollen Cakes - a recipe from Ancient China

pine pollen - two tablespoons

honey

This is a delicacy of late spring, and Chinese sometimes eat pollen as a nutritional supplement, processing it to make the nutrients more digestible. The result is a tan powder with deeper flavour and a little bitterness.

Pine pollen can be collected straight from the pine trees in spring. Pollen cones form on the end of branches, looking like miniature pine cones. If they are firm to the touch, they are still green. The trick is to catch that all-too-brief moment when they ripen and the pollen flows.

You can collect it in a glass jar by shaking the pollen cones. Or you can buy it, if you find a source. About a handful or two is enough, you do not need a whole bag of it.

Pour the pollen into a mixing bowl with high sides. Add a spoonful of honey and slowly stir this in. Eventually, the mix should just hold together when squeezed. Shape it into a few small cookie shapes and taste.

This recipe will make very little cakes, just to give you a taste of the exotic flavour of pine pollen. Which is why I included a second one, to match the Byzantium part of this story.

Sweet Wine Cakes - Byzantine recipe

Ingredients:

450g flour

2-3 tablespoons sweet white wine

a pinch of ground aniseed

a pinch of ground cumin

50g lard/butter

25g grated cheese

1 beaten egg

12 bay leaves

2 teaspoons baking powder

Method:

Moisten the flour with the wine and add the aniseed and cumin.

Rub in the lard or butter and grated cheese and bind the mixture with egg.

Shape into 12 small cakes and place each one on a bay leaf.

Bake in the oven at 200oC for 25-30min.